|

Copyrighted Material -CLICK for information |

|

Back |

|

Robert Maguire

(1921 - 2005) By Thomas Clement |

|

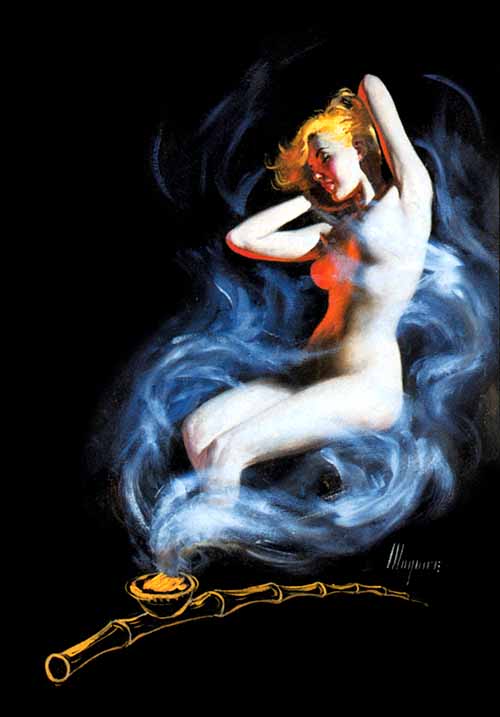

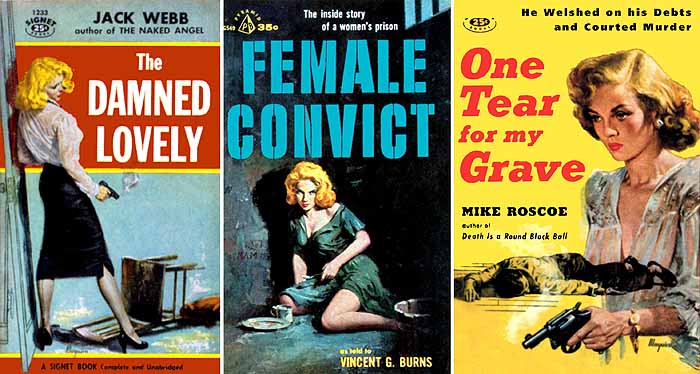

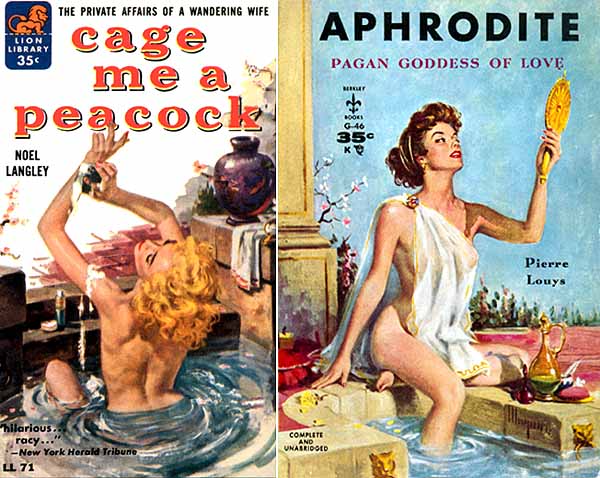

Fantasy Blonde: Black Opium (1958) Maguire - 001

|

|

"Why did I leave the paperback business? I got out ’98, ’99. They wanted the paintings to look just like photographs -- couldn’t even tell from the brush strokes. They didn’t want me to paint like me anymore. Can you imagine? By that time I was supposed to be well known, but these people (publishers) had no clue. Basically, the sales force became the most powerful element. If a book sold well, the next 4 or 5 books had to be just like it. There’s no future in that. Not every artist has a great new idea all the time, but frequently they do! And they fired the good art directors (too much money) and hired second-string art directors who didn’t have any real clout with the publisher. The good art directors could take a young artist and help mold him." It’s impossible to imagine that publishers didn’t want Robert Maguire to paint like Robert Maguire. From the late 40s, sporadically through the sixties, and back with a vengeance from the 70s on, Maguire’s paperback covers sold books far more than the books’ authors or titles. His ability to capture a sexy girl, often holding a gun, a knife, or even a voodoo doll, is instantly obvious. His women were always intriguing, whether the world was crashing around them or whether they were in decisive control. Each is glamour-page gorgeous. But talent for curvy dames was bolstered by a knack for dramatic action, bold and exotic colors, and striking throws of hues and shadows; these enticed millions of readers to do what they were supposed to do: buy the books. Maguire often set his women against some muted slab-gray background or low-key pattern of jagged screens, but just as often he stood them out against deathly greens, bloody reds, or morguish blues. Of course, basic black also served him well, as for what has become a signature piece, Black Opium. |

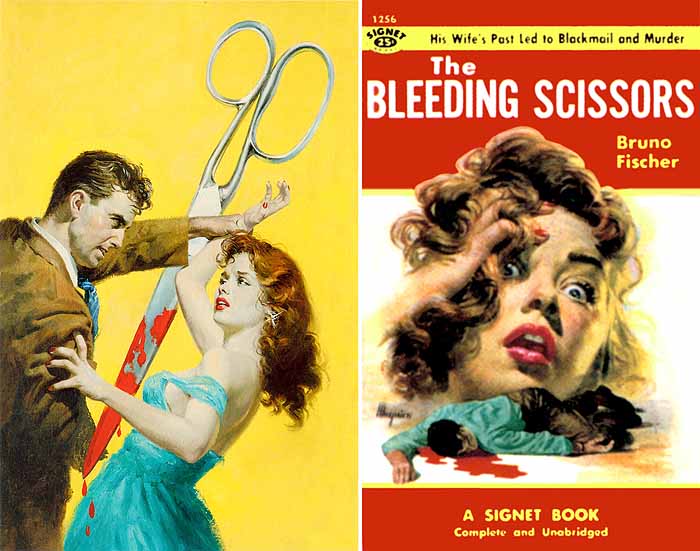

| Rejected painting for The Bleeding Scissors and the accepted version at right. Was one somehow less gory than the other? (1955) Maguire - 002

|

|

His Father’s Influence Unfortunately, none of his father’s art survives. "My father collected a lot of pictures of Europe — Italy — which in my later years my wife and I visited and I got a feeling of nostalgia. My father never had the wherewithal to travel like that and here I was his son and fulfilled his dreams." |

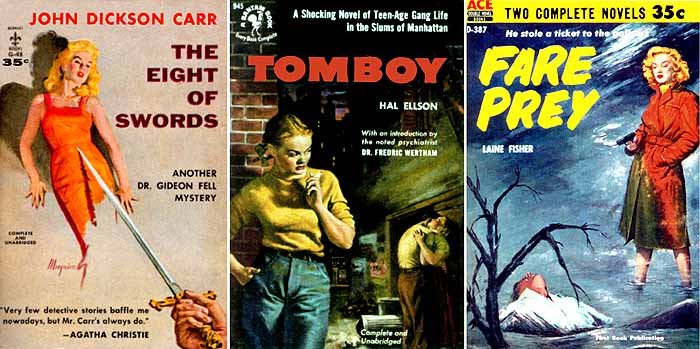

| She's Trouble, I Tells Ya. Trouble! The Eight Of Swords (1950), Tomboy (1951), Fare Prey (1959) Maguire - 003

|

|

Italy and he Fighting 88th The Brits left the 88th some lovely welcoming treats. "The British defecated in their stone shelters as a special gift to us when he moved in at night to take over (much to our distress). I don’t think they liked us Yanks because we were making time with their women, you know, over-sexed and over there." But he doesn’t hold a grudge. "They were magnificent soldiers. Brave. I saw them in a truck convoy going up one of the main roads. The Germans started shelling them and they never even got off their trucks, just kept driving through, all bare chested, their helmets on. They were the 8th Army that fought all across Africa. We have to give them their due." Maguire was a crack shot with the .30. "I was very accurate, but couldn’t always tell what I was shooting at, which could be a problem." Maguire made his first professional "sale" in the Army. "I did a couple of drawings of these beautiful roses and the commanding officers made me draw roses for them so they could send them home on mother’s day. That was my first commercial effort. I didn’t get paid, but I got some benefits out of it. I didn’t have to do KP." |

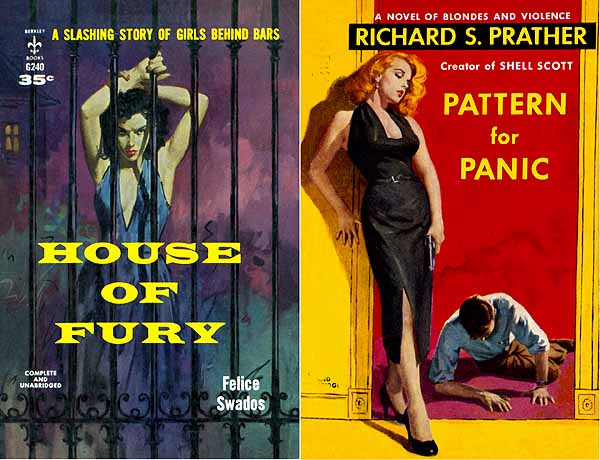

| Lurid titles and sultry poses. House of Fury (1952), Pattern for Panic (195?) Maguire - 004

|

|

Women on the verge of a Noirish breakdown:

|

|

Small-Town Guy in the Big City "I tried to get into Pratt’s University in Brooklyn, a very well-thought-of art and engineering school. And this huge woman called Mrs. Everest, about 6 feet tall, very severe, white hair, she took one look at my work and suggested I return to Duke University to continue studying what I was originally studying there. Years after when I earned a modicum of success, I wanted to go back and rub her nose in it, but never did. Probably best. She might have lifted me up and shaken me." And what would Maguire have aspired to had he listened to Mrs. Everest? He didn’t consider any other options: art was the only alternative. And he was presented with a lucky break to get into something a little higher than what Everest offered: a seat in Frank Reilly’s class. First, Maguire had to show his artwork to a friend who’s father knew Reilly. The father, Ernest Bauman, looked at Maguire’s portfolio, but wasn’t much impressed. "At least you have a steady hand." Not a glowing approval, but it was enough for the father to recommend Maguire to Reilly. "It was a miracle because there were so many people waiting to get in. I hadn’t even heard of Reilly at all so it was quite a bit of luck that I got in. I knew quite a bit about the Pratt in Brooklyn but not much about the Art Student’s League (where Reilly taught). It was actually a democratic institute run by students. The League is a classic school. You read an artist’s resume and 9 out of 10 of them studied there on 57th Street. |

|

This should have been the movie poster for: Hotel New Hampshire, but it was used for the paperback (1982) Maguire - 006

|

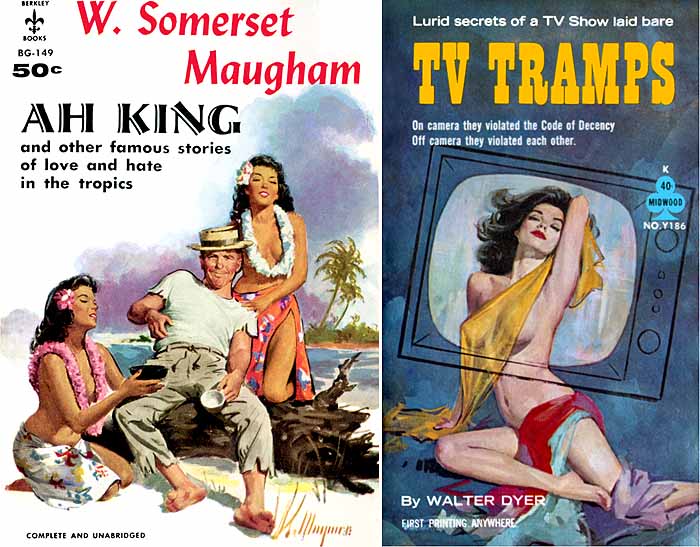

| Ah King (1958), TV Tramps (1962) Maguire - 007

|

|

"I remember my first day in class and I was relegated to a seat in the back of a class of about 60 people. It was a dark and rainy day and they had an elderly black man sitting and I could hardly see him. From where I was and because of the day, all I could see were his eyes and his teeth when he smiled. I was all ready to go home. But I stuck with it. The next week we had a classic woman model. It was 9 months to a year before you could learn how to draw classically as Reilly wanted us to do. We always tried to laboriously copy the model and you just cannot do that. You have to learn from the way the model poses, the line of action, and that took almost the whole year. Very few failures. An astonishing performance rate. Reilly said he could teach you in about a year and it was true." Maguire considers himself a small-town New Jersey boy. "I never really liked the city. There was this bohemian look at the Artists Leagues in the 40s after WW2 was over. I’d ride into town with some business men on the same bus they caught in my town and we’d get off and there would be all these artists and models with that bohemian look, and I’d go right past, I didn’t want to admit that I was going to go in there. Of course, today I’d strive right in and I would brag about it, but then I was trying to be ‘respectable.’" Reilly’s fellow students turned out to be Jimmy Bama and Clark Hulings. Why didn’t Maguire move West as so many illustrators did in the 60s and 70s? "You know what? I would never think there was anything admirable to painting a cow or a horse. A cowboy, maybe. But I think I liked painting beautiful women better so cowboys and horses didn’t appeal to me. In fact I have a very good friend, John Leone, who was very successful out there and he couldn’t paint a pretty girl to save his life. So? But he doesn’t resent me for it (laughs)." Of course, he still needed a horse for certain paintings. "I took a camera out one day and shot three or four rolls of pictures of this one horse in as many poses as I could and that was my horse reference for the next several years. I used that one horse a lot. But he never got a nickel in residuals." |

|

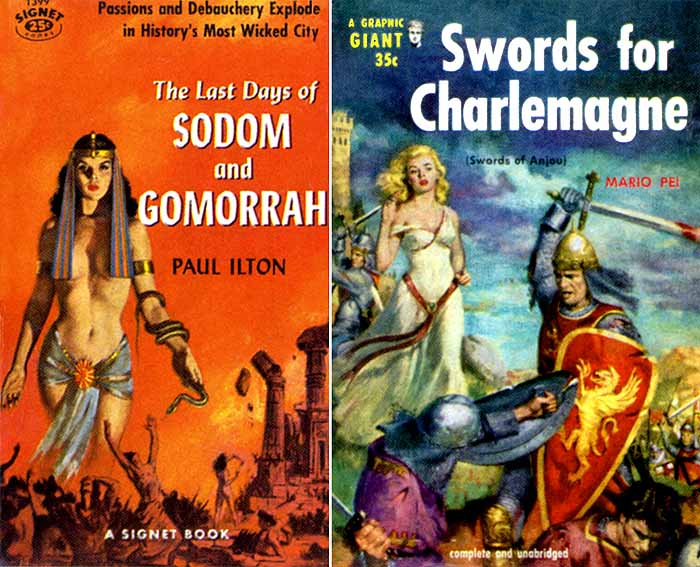

Historical Hubbub

|

|

The Paperback Years "I never had time to read the books. They gave me a very brief synopsis. Color of the girl’s hair. A hint about how sensuous they wanted it. That they didn’t want the girl to be a tramp or cheap, but a good looking woman. Obviously if it was a good book with a woman of sterling character, you couldn’t depict her as cheap. "They’d tell you if they wanted the clench (illustratorese for a man and a woman in a close embrace, maybe even close to kissing, but with both faces still clearly seen; not an easy picture to paint) or a pre-clench where they’re touching, but not too close. "I had this one model, very, very beautiful girl and very professional. She’d say, ‘How do you want me, zonked out of my mind or just mildly intoxicated?’ She had it all down pat. She’d go into one of these sexual trances and look like she was crazy about the guy model." |

|

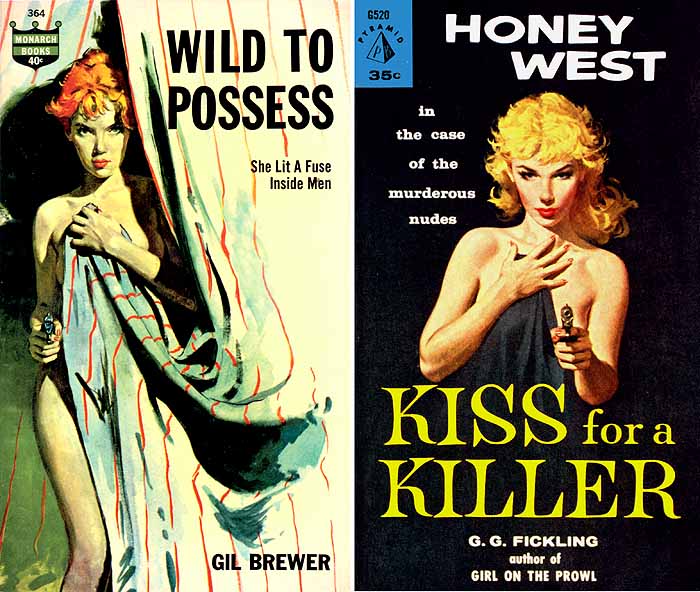

Girls with guns, Maguire patois, and a sure-fire book mover!

|

|

Maguire: How he worked Maguire worked on board, oil being the medium of choice (which he still prefers, but now applies it to canvas). "I always worked in oil except for one period when I did watercolors for the greeting card company." "Normally, I'd do about three paintings a month, but once they were in a real deadline, a real bind, and I turned one around in three days. I could do it that fast, but it wasn't ideal!" Separate Cabins (1983) Maguire - 010A

Separate Cabins |

|

Anatomy well learned

|

|

Real Romance "The models were very ‘active.’ They weren’t real. A lot of them were on drugs. I had one girl posing against a backdrop. She put her arms over her head and slowly slumped to the floor. I had to go over and shake her awake in order to finish the shoot. We had deadlines." Unfortunately, the first marriage didn’t last, though his second did, thanks to an introduction to a lovely woman by his friend, Leone. "I was divorced and John introduced me to an available lady whose husband died. That was over 20 years ago when I met Janice." They’ve been happily married ever since. "My friends and I were mostly in paperback books. The magazines were dying, mostly due to the advent of television. But we couldn’t wait to get the magazine copies and see what guys like Coby Whitmore were doing. All these great artists, Whitcomb, Al Parker, Bob Peak, Joe DeMers. We weren’t allowed to be that sophisticated. They could do this intricate design work. We tried to do use some sophisticated design and the paperback guys would say, 'Why don’t you just show the girls with the big boobs.’ I used to work with a very crude individual -- he shall be nameless -- he was an art director -- but one painting he wanted the gown lowered on the woman, ‘show more cleavage.’ So I’d lower it and he’d want it lowered some more. Well, another quarter of an inch and I’d be showing the nipples. That’s anatomy! But still, ‘Well, make it a little lower.’ Any lower and her breasts were down around her stomach. And then he wondered why the girl didn’t look quite right. But you couldn’t argue with some of these people (though of course, I did)." |

|

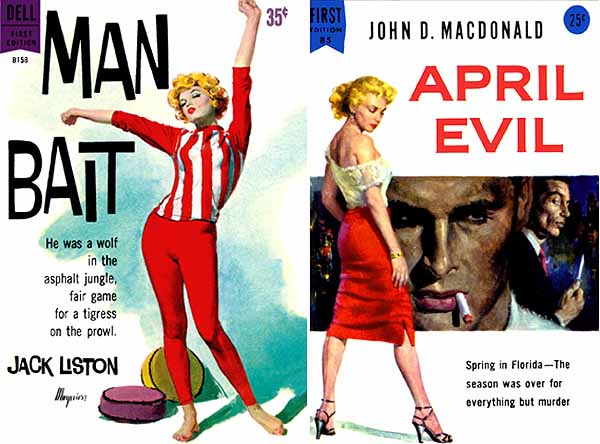

From the Asphalt Jungle to Spring Break.

|

|

Maguire was never asked to copy a specific style or artist, though for a while, publishers wanted Jim Avati clones. "A few artist could do it with enough skill. Jim Meese could paint a little bit like Avati when necessary." Maguire didn’t often venture out of the paperback world; no advertising work, for example. But he does have one story: "I did a movie poster with Marilyn Monroe. I painted her with rich, creamy skin and they wanted her with her skin brown, looking like she had a good suntan. They started to read me the riot act and I told them to cut that out. At that, they shut up like a clam, but I don’t think they ever used the painting even though it was paid for. I don’t have a copy of it. I walked away from that and never looked back. A lot of people suffered working for those guys (the movie studios). You made good money, but were virtually a slave. Never signed your work." "Pocketbooks was like that, too, though. The owner forbid artists from signing their work. I signed it anyway. I never got any problem with that because we had a good art director, Milton Charles, an excellent, excellent man. He used to pay $3,000 and $4,000 for a cover routinely for fairly well known artists. I made six figures under him for a couple of years. "Berkeley Books. I thanked the art director some years after the fact for giving me so much work over the years and he said, 'You always did satisfactory work. And you were always on time.' So it seems that being on time was as important as doing a classy job. It hurt my feelings." He laughs. |

|

Maguire rarely ventured into the magazine world, which is a shame.

|

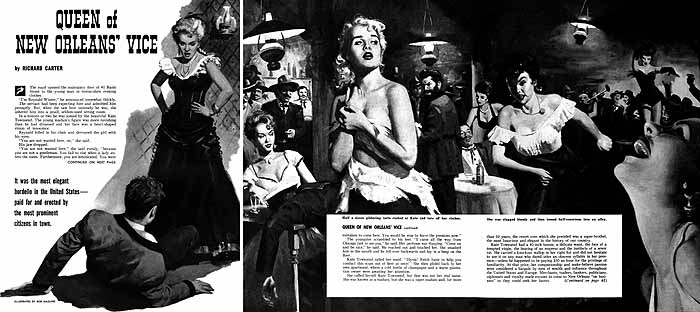

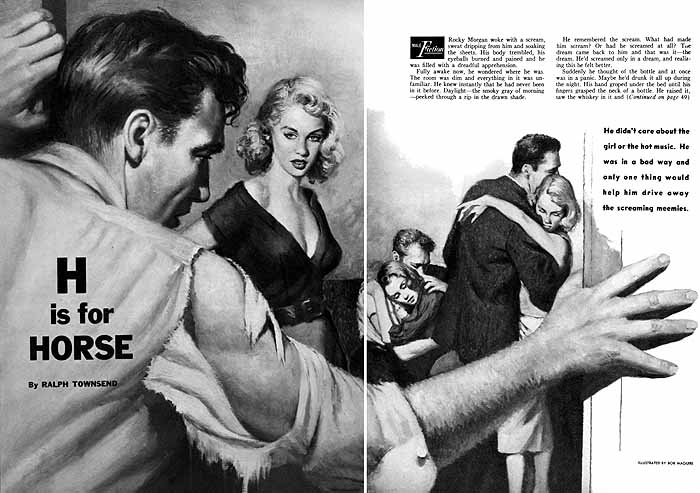

| Male, "H Is For Horse" (1955) Maguire - 014

|

|

Greetings "So that’s where I went next. It was a beautiful place to work. I learned so much there. We artists didn’t always paint pretty girls being molested by bad guys. There we did the Magi and the Bethlehem scene and the flight out of Egypt. Greeting cards were painted the actual size of the card which is why gouache was chosen. 4x5 or 5x7. You can’t do that well with oil; you couldn’t get all the detail you wanted as you could with gouache. I’d never painted in anything but oil before, so had to pick up watercolor in a couple of weeks. "Norcross’ work was very distinctive. Of course, greeting card art was considered a step-down from paperback covers, just as paper covers were considered a step-down from magazines (the first greeting card Maguire featured his daughter kneeling along with other children)." "I ran into Walter Popp while I was still at Norcross and Popp said, ‘Bob, come on back. The paperback business is better than it ever was.’ So I did, and I made a lot more money than I did before." |

|

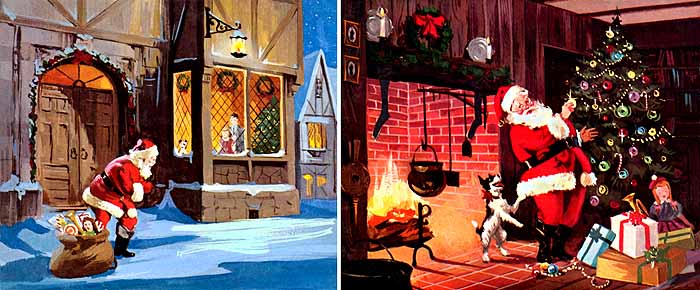

Four examples of Maguire's Norcorss output (1960s) Maguire - 015

|

|

Two of the four commemorative Lincoln plates Maguire (1993) Maguire - 016

|

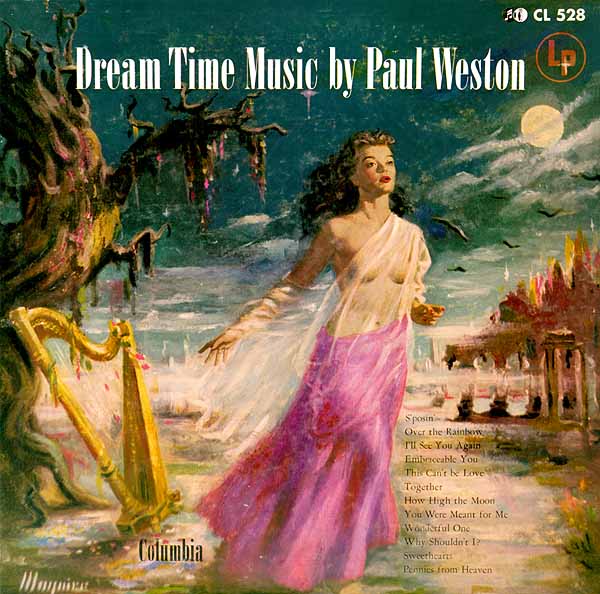

| Maguire was also perfect "lounge" style LP covers, This for Paul Weston (1950s) Maguire - 017

|

|

Maguire's output falls into three periods: the hard-boiled noir novels, usually with two never exhausted themes: a bad-girl doing (or about to do or just having done) a dirty deed or a good-girl in trouble. This period ran from the late 40s to the early 60s. The 70s and 80s saw still more crime covers, but broadened to include westerns, medical romance, and even sci-fi. Maguire also did paperbacks of best sellers like those of John Irving and Herman Wouk (the paintings for these show a movie-poster sensibility and it's a shame he wasn't given a chance to do film work). Most of my work is long gone. "People would come up and visit me before I realized that these paintings had any value and they would buy 10 or 20 of them for $50 or $100 a piece." |